ARMERING #2: MURO

From the moment their debut album Ataque Hardcore Punk arrived back in 2017, Bogotá's Muro stood out with a fierce yet focused take on hardcore punk. The album was released on Oslo-based label Byllepest Distro, and as a local punk fan, it was extraordinary to see how the release of the Muro album was followed by a gush of punk activity in Oslo. The subsequent flow of first-rate releases on Byllepest Distro seemed endless. The label also facilitated for new local bands who were forming, alongside inviting touring bands from all corners of the globe to Oslo.

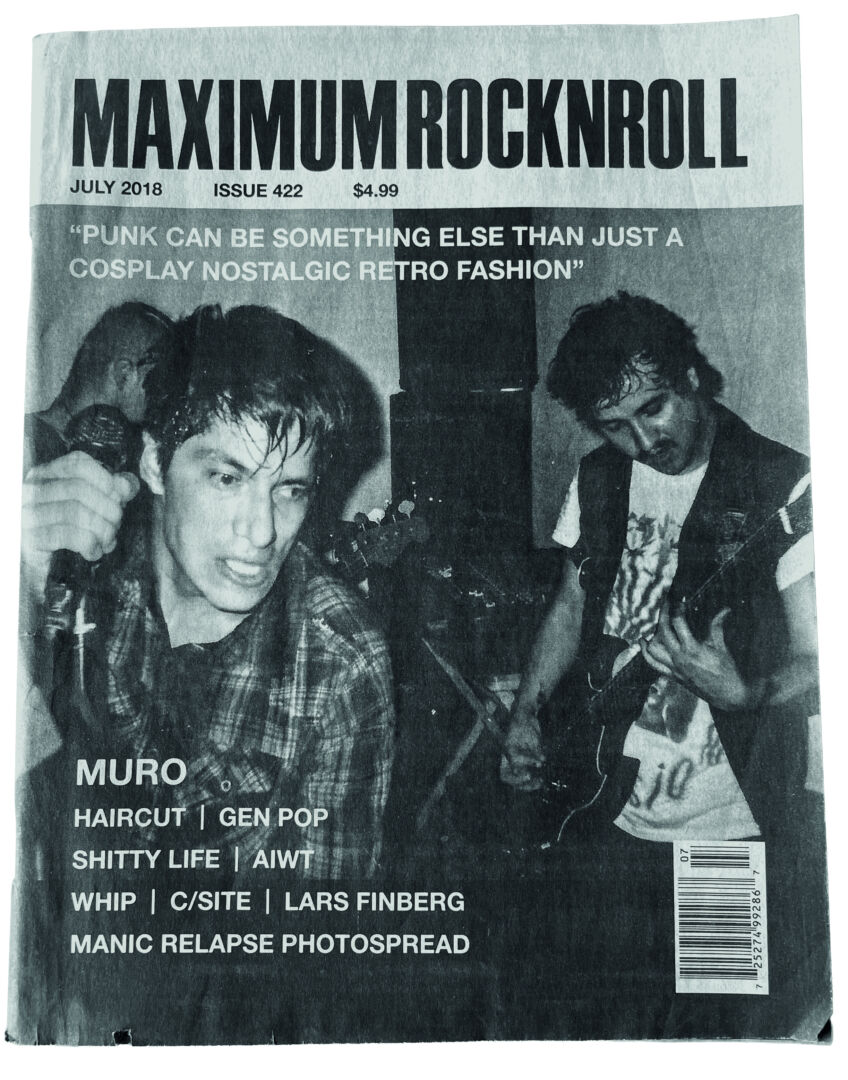

Muro themselves made the trip to Oslo twice – once in the autumn of 2017 at Goon Bar, and the following summer at the two-day festival Byllepest Hardcoreweekend. In between the two shows, I interviewed Muro for one of the final physical issues of Maximum Rocknroll. In a candid conversation, the Bogotá crew went into detail about the Rat Trap collective that Muro originated from, the current state of affairs in Colombia both punk-wise and politically, and more.

Since then, Muro have either been on the road, in the rehearsal space or in the studio – be it a recording studio or a screen-printing one. Currently, the band are on the Australian leg of their 2025 tour which has already swept through the UK, Ireland and Central Europe, with Japan as the final destination in November. A few weeks back, I found myself in Poland for Muro's show at the Syrena squat. Seven years had passed since our MRR chat, so I figured it was time to catch up.

This interview is taken from the coming second issue of the Armering fanzine. Get in touch here to order.

It’s so nice to see you guys again! When we did the Maximum Rocknroll interview in 2018, you had only done one tour. How many tours have you been on now?

Rafa: Right, that was after our first European tour.

Carlos: I think we’ve done eight tours now.

Eight tours in eight years. This year, you’ve already completed a spring tour of UK and Ireland. Now you’re in Europe for some weeks, and then you’re off to Japan and Australia. You’re more active than ever.

Rafa: I don’t really think we ever stopped. We keep getting requests, so as long as we can make the tour sustainable, we’ll do it. In between tours we have a lot of ideas in movement. We’re making riffs, writing lyrics, rehearsing, recording demos. And when not doing the band, we spend time screen printing at Rat Trap.

How do you feel Muro has evolved over the years?

Rafa: I feel like we’ve evolved musically. We still have the same influences when we started, which is 80s hardcore punk, but at the same time we are always appreciative of hearing new music. The members in Muro listen to different music, discover new music, and bring it into the band. Also touring has made us tighter, socially but also musically.

I feel like every album has its distinct sound. Ataque Hardcore Punk was quite straight-forward and raw, Pacificar had more depth and ambience, and Nuevo Dogma – your latest album, from 2024 – is very chaotic and has a fresher take on song structures.

Carlos: Each album was recorded in a different way. The first album, Ataque Hardcore Punk, was recorded by Santiago from the band Primer Regimen. He’s a professional. We didn’t know much about recording at that point, so the only request we had was that we wanted to record most or all of it live. Then with Pacificar, we recorded it on a four-track cassette. Most of it live, but we overdubbed some parts because we didn’t have enough channels. That one was recorded by Sergio Gonzalez, a good friend. Nuevo Dogma was recorded before Juan David moved to Barcelona.

Juan David: Again, touring so much as we have, has led us to discover new sounds all the time. Playing concerts in different places, different venues and with different bands has broadened our horizon. We’ve also got more experience playing our instruments and also discovered new ways of playing them. We’ve grown both as a band and as individual players. I remember telling Carlos just before this tour while we were practicing the guitar parts, «wow, how much the sound has changed since the start.» It would be boring if not!

Carlos: By the time we were ready to record Nuevo Dogma, we knew we wanted to record it ourselves. I did the mix, which was a learning process for me. The songs on it are a little bit progressive in a sense, so we wanted the song structures to come through in the mix, but we didn’t want to polish it too much either. We learned to listen to punk through tapes, and the great thing about that is that it demands your attention because not every detail is immediately transparent. You have to pay attention. We don’t want to become apart of this systemisation, homogenisation of how music is done, where people use the same pedals, same software, same mastering engineer.

You’ve always been more DIY than most, but with Nuevo Dogma you took it a step further. Recording and mixing it yourselves, doing all the layout, making two poster inserts et cetera.

Carlos: I felt like with Nuevo Dogma, we got a chaotic, but focused sound. Not experimental as such, but it’s not easy listening either. We wanted it to draw you in and to demand your attention. It shouldn’t be like hearing songs on a playlist.

It’s funny you mention experimental. For the Maximum Rocknroll interview, you mentioned that the only other subculture in Bogotá who accepted punks, was the experimental music scene. Have you taken inspiration from that scene in the newer songs?

Carlos: Me personally, no.

Rafa: Not on a sound level, but I’ve been inspired by watching how experimental bands play together. So more than being inspired by their music, I’ve been inspired by their approach to creating and playing music. I also listen to a lot of heavy metal music, which I try to put a bit of in my drumming in Muro. But only if it works together with our sound, not just for the sake of doing it.

Darcy: I think each album has been full of experimentation. The first album for us was classic-sounding, but since it was our first work, it was also the first encounter of ideas between us as members, so the experiment was to try and make our separate ideas work together. With Pacificar, the experiment was that we set out to make an album from start to finish that felt complete, with its own atmosphere and mood. I also had more vocal training, so my use of the voice was broader and more complete. With Nuevo Dogma, we wanted to have a combination of simple songs and also more elaborate ones. More intros and outros.

How about the lyrics, how have they evolved?

Carlos: We try to tell stories with our songs. Of course many people do not understand our lyrics, so the songs need to somehow have the atmosphere of what we are trying to say. We spend a lot of time on that. Things have definitely changed from album to album, but the most important change in the band is that we have become closer together. We have worked together, lived together, played together for almost ten years. All this can crush a band. But we have founds ways to deal with each other’s personality, and that’s a very valuable lesson. Also in a broader sense, because through collective action, we have also found what is personal for each of us.

With Nuevo Dogma, you published a manifest along with the album, which outlines the idea of «nuevo dogma» and what it represents. Can you tell us a little bit more about that?

Carlos: The idea of «nuevo dogma» comes from our experiences. Like I said, tension will arise in a band when you spend so much time together and create. So learning how to deal with tension – with care – and to continue playing, is something that has given us a lot of tools to deal with each other as humans. We live in a world where there is a constant battle for power from all political sides. If we replace one system of power with another, it will just breed new ways of misery and exploitation. It’s significant that we do this interview here, in Poland, because where we come from, socialism and communism has represented a hope for another kind of model, a fairer one than the one we have today. A desire for something different. But then you come here and you see another face of power, represented by communism, which has been used to oppress people just like capitalism. The lesson we learn from this is that the punk approach is right – self-organisation makes sense. «Nuevo dogma» means that we believe in self-organisation and self-determination, like for example through a handcrafting revolution. Doing it yourself, on a personal level. Every macro model that insists on being superior will continue devastating and exploiting the earth and the beings that are on it to display their power.

Poland’s history with communism is certainly a contrast to your experience in Colombia. Last time we spoke, you mentioned how Colombia have never even had a leftist government.

Carlos: We played in Sopot two days ago. We found graffiti with a swastika and a hammer and sickle that were combined. I think it’s an example of how people here understand that every system of power can be used for repression and control. I’ve said before that Colombia is a perfect model for a dictatorship, because you don’t need to implement it explicitly. You don’t need a military junta. The consumerism and oppression is so strong and has been going on for so long that people don’t know anything else, so they willingly and voluntarily participate in it.

When the last interview ran, the Colombian guerrilla FARC had just demilitarised after a peace treaty with the government, then led by president Juan Manuel Santos.

Carlos: Some of us grew up in the city, and were fed with propaganda from the government that the guerrillas were responsible for everything that is wrong in Colombia. Eventually we understood that the people in the guerrillas were organised farmers. They didn’t choose to spend 60 years roaming around the mountains of Colombia fighting the state for fun. Since the treaty came into effect, the state has been betraying the terms of the treaty. Many people who were previously in FARC have been killed. The treaty didn’t change anything for the victims. A lot of the farmers who were in FARC have adapted to the capitalist system after the treaty, opening businesses and so on. It’s of course better for people to earn a living that way. But it ends up drawing indigenous people into city life, depriving them of an autonomous living that does not depend on capital, and makes them a part of the tributary tax system. And so the system is legitimised. That’s the moment we are at.

Here in Poland, there are a lot of refugees from Belarus and Ukraine, also in the punk scene. In Colombia, you have Venezuelan punks that have fled their home country. Last week, the Venezuelan politician won the Nobel Peace Prize, like Santos did after the treaty with FARC. What’s your reactions to this?

Rafa: I think Machado’s campaign is a theater, it’s a political movement designed from the US. It’s exploiting the people. And now, you see the complicity of the Nobel Committee in legitimising that movement. There’s so many eyes fixating on Venezuela now, because they want to get the resources in the land. They’re using the Nobel Peace Prize to clear their hands of the exploitation. It’s the same strategy from Netanyahu when he nominated Trump for the Peace Prize.

How is the Bogotá scene now? I remember you told me that you had some touring bands coming down. Glue, for example, who you were driving when the brakes on the car broke.

Carlos: Since last time, we’ve created a festival called Asfixia. It’s been going on since 2019, and we’ve had 15 or 16 editions so far because we did it twice a year in the start. Bogotá is really alive and well. We don’t do many local shows because there are too many. There’s opened more DIY spaces, so each weekend it’s maybe four or five shows.

So you’re not alone at Rat Trap anymore.

Carlos: No. We’ve never been, though. Every big city has several scenes, around different genres, ages and so on. The Colombia scene is big now, a little bit segmented, but there are events that gather people. Last weekend we had a self-organised festival called Punk al Parke, a parallel to a big public rock festival in Colombia called Rock al Parque. Rock al Parque started as a self-organised festival, but eventually it became very institutional. And the role of institutions is always to establish hegemony and set in stone one way of doing things. So Punk al Parke was formed as a protest, by both young and old punks combined. It’s really good.

How about the plans for Muro, how is the future looking?

Juan David: We’ll see after the rest of the tour. First, we’ll probably sleep for months.